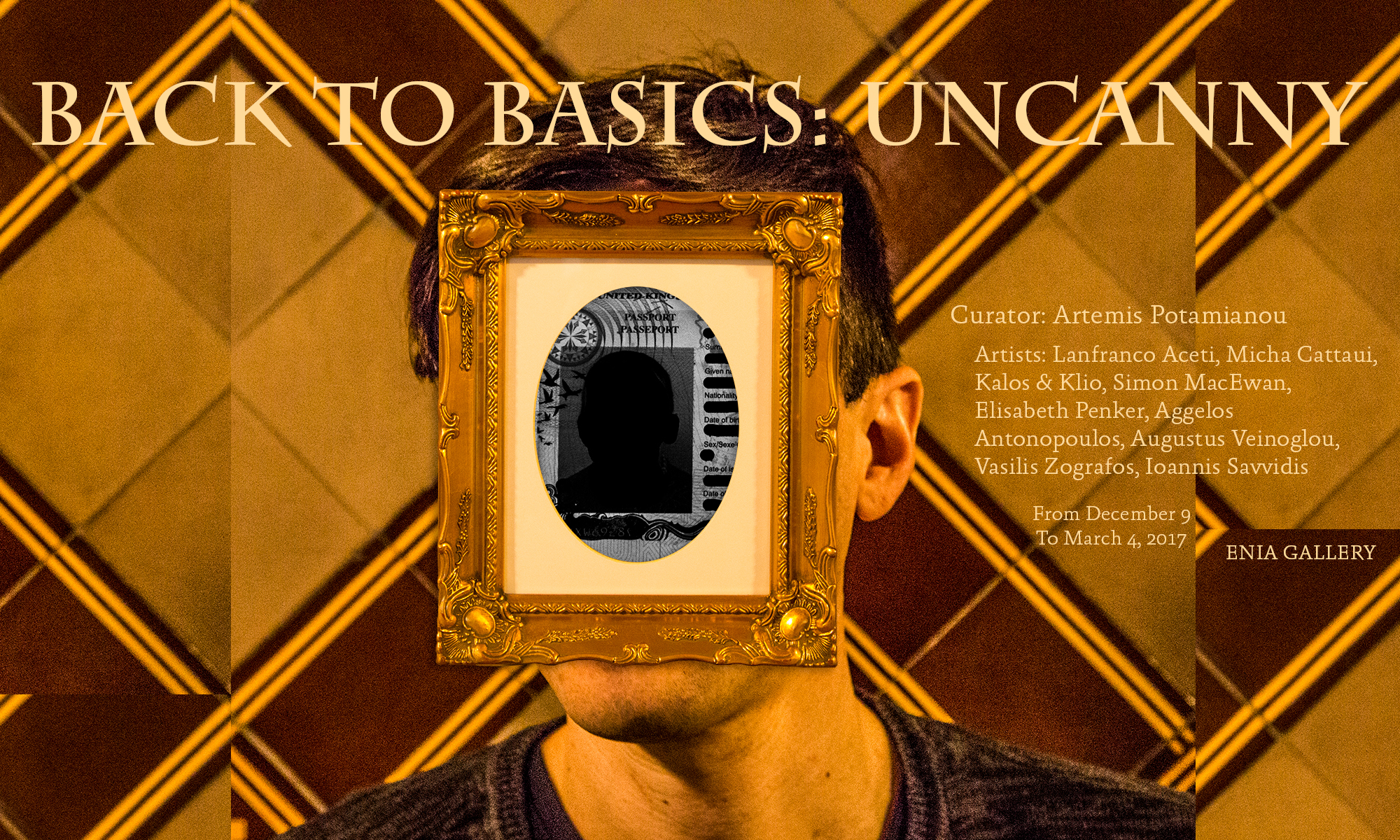

A new exhibition titled Back to Basics: Uncanny in which I have a set of artworks and an installation. This group show curated by Artemis Potamianou sees the participation of Lanfranco Aceti, Misha Cattaui, Kalos & Klio, Simon MacEwan, Elisabeth Penker, Aggelos Antonopoulos, Augustus Veinoglou, Vasilis Zographos and Ioannis Savvidis. The exhibition, the first of a two parts show, at the Enia Gallery, from December 9, 2016, to March 4, 2017, presents a series of artworks based on artistic practices that are exploring the uncanny aesthetic basics of contemporary art and activism. Admission to the exhibition is free.Official opening: Friday, 9 December 2016 at 20:00. Exhibition duration: 9 December 2016 to 4 March 2017. Enia Gallery opening hours: Wednesday – Thursday 11:00 – 19:00 Friday 11:00 – 20:00 Saturday 11:00 – 16:00.

The official curatorial statement for Back to Basics: Uncanny by Artemis Potamianou and released by Enia Gallery follows.

The uncanny is a complex concept that Sigmund Freud analyses in Art and literature, first published in the autumn of 1919, and it has been a source of inspiration and debate for art and philosophy ever since. The exhibition Back to Basics: Uncanny explores various approaches to the concept as defined in Freud’s essay and how the meaning of the word Uncanny is reflected within artists’ creative processes.

The Uncanny conveys the notion of the alien, the strange and the uncertain, but its uniqueness lies in its direct connection to the feeling of an experience at once familiar and well-hidden. According to Freud, something completely unknown cannot be uncanny; it must have references to something older which has been alienated.

In the chapter “Das unheimliche” (The Uncanny), Freud examines the relation of the German word heimlich (familiar, not paradoxical) and its logical opposite, unheimlich. Freud, by looking up the etymology of the two words in the dictionaries of various languages and collecting stories, experiences and situations that trigger a sense of unfamiliarity, concludes that the uncanny belongs in the category of the scary-weird which has been repressed to the point of becoming unfamiliar.

The semiological interpretation of ‘heimlich’ goes in the direction of ambivalence, until it coincides with its opposite — Unheimlich: “the unheimlich is what was once heimisch, home-like, familiar; the prefix ‘un’ is the token of repression”.

Artists have often tried to convey this special feeling of the Uncanny in various ways by joining parts-elements of a text or image in unexpected ways. In the exhibition Back to Basics: Uncanny viewers will be able to discover ways of presenting and interpreting the Uncanny through the work of nine artists.

Lanfranco Aceti’s Who the People? was first presented at Chetham’s Library, where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel worked together on the Communist Manifesto. The work examines the notions of individual identity, personal data and post-capitalism. The exhibition features four digital portraits where the faces are covered by parts of ‘deleted’ data, producing a narrative about the process of deleting humanity. The viewer is unable to tell the faces and the stories of the depicted persons, the connections among them or the information on display, and the result is a strange, awkward, uncanny sensation.

A different approach to portraits with missing parts we find in the works of Vassilis Zografos from the Missing series, which focus on variations of traditional Greek dress and grooming. To Zografos, these are painterly renderings of the elements of Greek folk tradition — the collaborative spirit, the coming-together on festive occasions in a mood of participation and congeniality. The faceless portraits appear as strange symbolic depictions of women where, as in Aceti, the viewer is called upon to discover and fill in their narrative.

Micha Cattaui’s Tour de force attempts to reinterpret the famous statue of the Nike of Samothrace, with an entirely new and unfamiliar approach to this quintessential symbol of ancient Greek art and prized exhibit of the Louvre. The bright pink colour and the atrophied chicken wings in place of the statue’s characteristic appendages give a sense of ‘mutilation’ as part of the artist’s caustic comment on the colonialist transfer of one civilisation’s cultural heritage to another, more ‘powerful’ country.

Split Representation is a series of portraits by Elisabeth Penker, inspired by Claude Levi-Strauss’ text on Split Representation in the Art of Asia and the America. In this text Levi-Strauss compares cultures from different times that use identical elements in their representation of bodies and faces. Notably, a face is never depicted frontally but as two mirrored profiles joined in the middle to form a strange multi-sided view. This use of mirroring/doubling and distorting an image, as crystallised in the works of Penker, is to Freud a key constituent of an uncanny situation as it emerges through his analysis of the short story “Die Elixire”.

A kind of reflection is also present in the works of Simon MacEwan, thanks to a vertical axis of symmetry that runs through them. His Transit works explore the relations between form and essence, and the properties with which they invest the elements that carry them. The geometrical language of MacEwan hints at the spiritual and the mysterious in a world where the invisible forces of authority and the economy can throw contemporary man’s life out of control. The images of constantly changing clouds and waves are combined with lines and map elements to allude to the chaos of the world and man’s attempt to systematise it.

In the paintings of Avgoustos Veinoglou, familiar architectural structures are turned into uncanny sculptural labyrinths. The rock-carved dwellings of central Anatolia are presented as floating, dreamy worlds which incorporate elements of modern ruins and unfinished structures that engage in a dialogue for analysing and determining the concept of space. In his Metaformations, Veinoglou uses his artistic gaze to combine dream, geology and architecture in utopian spaces which are at once strange and alluring — the very sensation that Sigmund Freud describes as uncanny.

Architecture and the concept of space transformed into imaginary, illusionary places are also key elements in the works of Yannis Savvidis. The paintings in the exhibition come from three of his series — Decompositions, Garden and Stilalive. Imaginary adventures from the life of the Prussian neoclassical architect K F Schinkel and his fatal involvement with the modern-Greek reality, Flemish still-lifes and semantic elements from photographic montages come under the artist’s microscope to provide him with research material. Savvidis reproduces and distorts all these to create new narratives and interpretations which end up turning the initial material from familiar to new and uncanny.

In his work Meteoro, Angelos Antonopoulos abolishes the conventional laws of gravity. His work is a lyrical installation in the manner of the Cabinet of Curiosities — a microcosm, a kind of private micro-museum full of curious objects, or a “memory theatre”. [2] The construction of this surrealist edifice, an air-floating house surrounded by faded graphite portraits, generates a sense of mystery which is magnified by a colour palette limited to neutral colours. This structure, at once credible and implausible, leads visitors to focus mainly on the experience as if they were the audience of a weird theatrical play.

With their works from the Artificialia series, a term that points directly to human artefacts, Kalos & Klio take us into the logic of Curiositiy Cabinets, just like Antonopoulos. Here the strange portraits seem to have been subjected to an almost violent process of dismantling and rearranging human parts, arriving at an uncanny outcome. In this series the use of digital media is harmoniously combined with traditional engraving to complete the metaphysical nature of these disparate images. At the same time it raises questions around the concepts of natural and artificial, familiar and alien, experience and memory.

[1] Freud, The Uncanny, 245.[2] Francesca Fiorani, review of The Lure of Antiquity and the Cult of the Machine. The Kunstkammer and the Evolution of Nature, Art and Technology, Horst Bredekamp. Renaissance Quarterly 51, no. 1 (1998), pp. 268-270..